Making a Wooden Globe, page 2 of 4

by Marco Aurelio R. Guimaraes

marcoarg@terra.com.br

Having arrived at this point, it was time to begin construction.

Obviously the globe could not be a solid sphere of wood since the inevitable contraction and

expansion inherent to all kinds of wood would cause the whole project to become cracked and flawed.

That's why it was necessary to make it a hollow sphere.

Several possibilities were considered, tending towards a series of pieces turned on the lathe, the

same way in which we turn segmented bowls. While this seemed like a reasonable possibility, the

grain direction would cause the internal forces in the walls of the sphere to be distributed in an

uneven manner. For some regions the grain direction would run approximately parallel to the surface

while others would present end grain to the surface. Furthermore, since the contraction and

expansion of the wood differs according to the grain direction, the glue lines or even the segments

themselves would certainly fail.

Thus I decided to make the globe sphere in a very unusual way, not using a lathe, but surprisingly

with a table saw! This would solve the major part of the problem since the wood fibers would run in

a direction that would allow better distribution of the internal forces caused by the absorption of

humidity. Besides, with this approach, it would be possible to achieve a more consistent pattern and

color on the wood surface.

Accordingly, I precisely cut 48 blocks (shown in the following photo) whose faces defined perfect

rectangles. These blocks would form the future curved walls of the globe.

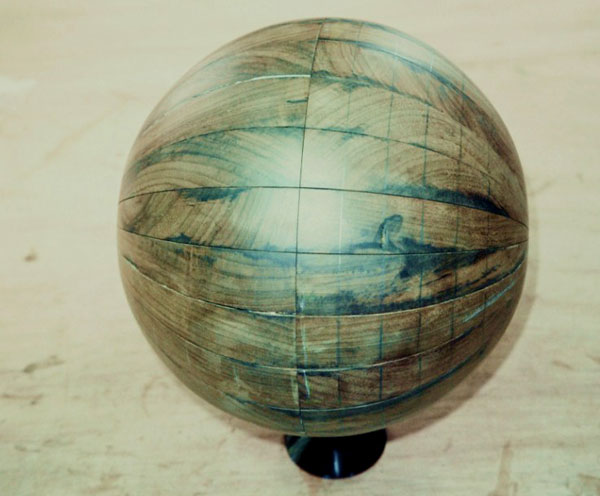

Thus the globe is basically a wooden sphere made of 48 identical half sectors of spherical calottes

[a sector of a spherical calotte is a solid figure similar to an eaten slice of watermelon], which

align with one another at the equator line, thus forming the 24 meridians.

Considering that it would require 48 identical pieces to make two perfect semi-spheres, it was

imperative to avoid even the slightest error in the angle sides. For instance, if I made each piece

only .04" wider due to a systematic error, the result would be multiplied by 24, meaning that the

last two sectors would overlap each other by almost an entire inch! If the error, on the other hand,

reduced the dimension of each sector, the result would be a one-inch gap between the last two

sectors assembled side by side.

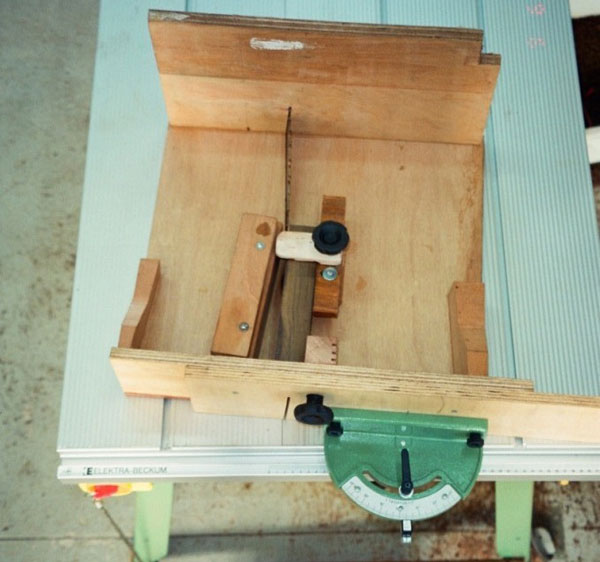

This forced me to search for a solution for the cutting process so that the angle of the blade and

the miter fence, once set in the table saw, would not be changed while cutting both sides of the 48

blocks. I calculated by trigonometry the angles for setting the blade and also the miter fence

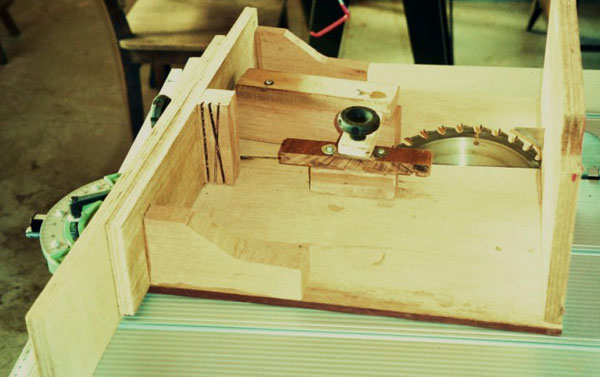

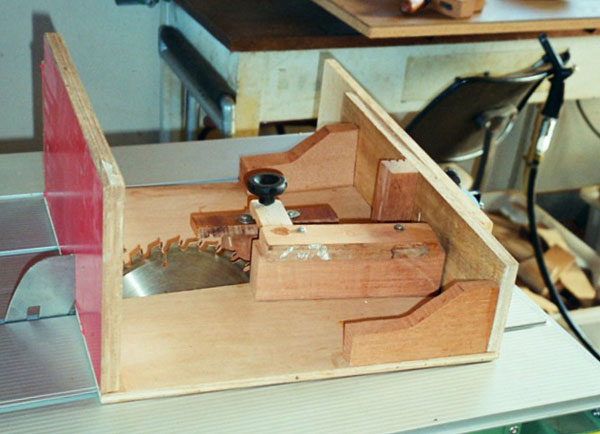

inclination on the table saw. I then made a sled jig from scrap wood in order to firmly hold each

one of the 48 blocks as it was being cut, as illustrated in the following photos.

Each cutting action provided the same exact angle (with no re-setting procedures) when changing from

a block to another, or even when flipping them end for end and face for face in order to cut the

opposite side. I used some thumb screws to fine-tune the first cut, so that the pieces would have

the same angle to exactly close the sphere when inserting the final 24th sector.

The next photo shows the 24 pieces, some of them shown after the cut in the table saw (such as the

first eight prisms in the lower line). The curved ones in the center row (shown in several

positions) have been further shaped by rough cutting on the band saw.

The wood species I used was a kind of Brazilian walnut (Ocotea porosa), locally called Imbuia, or

Imbuhia, that presents a very beautiful brown color and a charactieristic, pleasant-smelling odor.

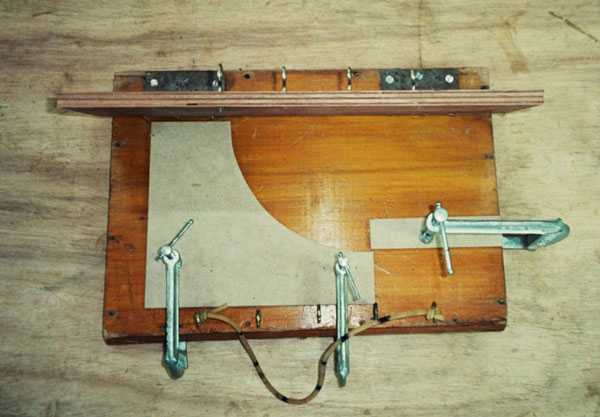

The gluing stage was a messy and challenging job since all the edge faces of the pieces were

inclined one in relation to the other. Besides that, the lubricating effect of the glue I used made

the surface edges so slippery that it was almost impossible to maintain more than two of them in the

right position at one time. Thus, I made another jig in which a kind of ringed lid secured the

sectors to be glued in the right position. In order to maintain an even clamping force, I used a

string (1/4" medical rubber tube) on which I marked equal segments.

That way, after being stretched, the equal segments of rubber would exert the same strength,

establishing an even pressure on the pieces being glued.

The sectors in several assembling stages and the hollow globe are shown in the following photos.

The intersection of the meridian lines in the North Pole and the upper sectors (north of the equator

line) match exactly the corresponding ones on the lower side, with no gaps.

I routed a small recess in one of the external edges of each semi-sector in order to accommodate in

the future a strip of gold that would enhance the meridian lines.

After being entirely assembled and glued, the two half spheres were sanded round and smooth in the

lathe.

Go to next page

Go to Wood News front

page

Go to previous page